A version of this article originally appeared on GW Today.

By B.L. Wilson

One of the first stories that Dorothy Butler Gilliam covered as a journalist just out of college was the integration of schools in Little Rock, Ark., as federal marshals sent by President Dwight Eisenhower accompanied black children to schools.

She stepped in to take the place of her editor at the black newspaper, The Louisville Defender, after he was beaten by a mob.

At a time when the country was undergoing revolutionary changes in race relations, the stories in Little Rock were among scores of historic milestones Gilliam covered in her reporting career that included being the first black female journalist hired by The Washington Post.

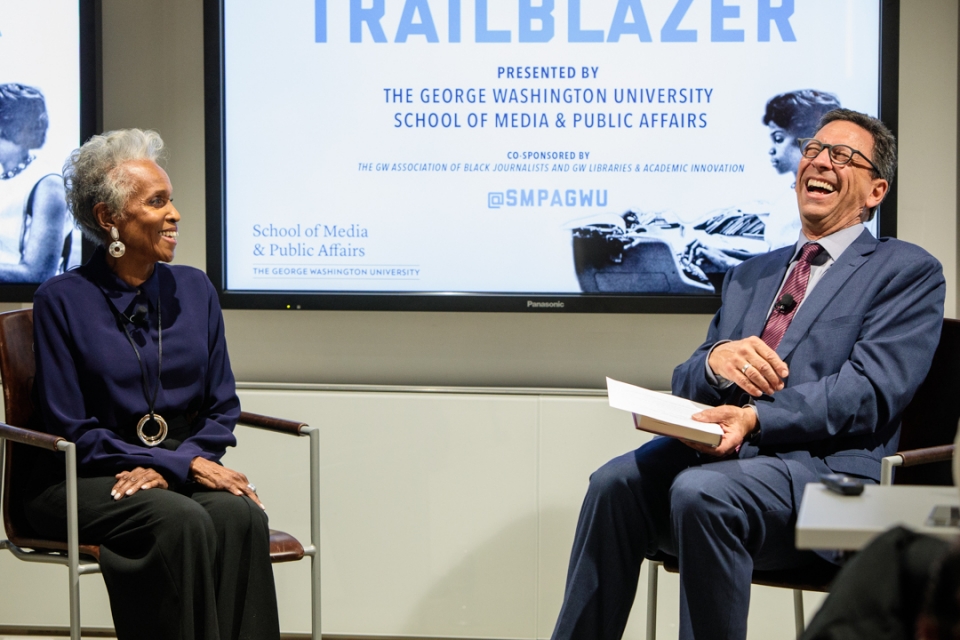

“There isn’t a glass ceiling that Dorothy met that she didn’t smash, and it wasn’t easy and sometimes it was scary,” said Frank Sesno, director of the George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs.

He first got to know Gilliam when she was director of the GW Prime Movers program, which brought together veteran journalists, GW SMPA students and high school students in the District of Columbia to create an intergenerational learning experience.

Sesno welcomed Gilliam Wednesday evening back to GW for a conversation about her new book, “Trailblazer: A Pioneering Journalist’s Fight to Make the Media Look More Like America“ at the GW National Churchill and Library and Center.

Gilliam’s journalism career was not one she imagined when she started out, “living almost like sharecroppers,” in the segregated South as the daughter of a minister and a mother who had been trained as a teacher but was forced to work as a housekeeper.

She started working at The Louisville Defender as a secretary at 17 years old.

“Journalism actually gave me the opportunity to see new worlds,” she said, taking her into the lives of Louisville, Ky.’s, small black middle-class neighborhoods, “seeing that there was a lifestyle probably two miles from my house that I hadn’t seen other black people have. Those things let me know that if I stayed with journalism I would see more.”

In 1961, after a sure and steady climb through college, stints in the black press, the Columbia School of Journalism and cultivating a contact at The Washington Post while on a cultural exchange program in Africa, she arrived in the nation’s capital:

Just 23 years old, I was won over by the magnificence of official Washington’s buildings and even the romanticism of street cars that daily clanged past the U.S. Capitol and on which I could choose a seat any where I wished unlike in the Deep South where I was born and the segregation was debilitating.

“I was about to dive into this sea of white men with two invisible weights that none of them had—race and gender,” she said.

She discovered an extremely segregated city that required constant maneuvering if she were to succeed at her assignment on The Post’s City Desk. Taxis often wouldn’t stop for her, making it difficult to travel about the city. So she wrote on the run in Gregg shorthand to avoid missing deadlines.

“’We tried but it wasn’t our fault,’” she imagined her bosses’ saying. “It was important to make it work, but also not to complain about it, not to come back and rail and rant.”

She wrote stories on poverty, welfare and the juvenile court system in the District of Columbia. Later, she headed south to the “land of black death, Mississippi, where black people had no rights that white people had to consider.” She described being stopped by two white men in a pickup truck with gun racks on the back. “I knew they could kill us.”

She was part of a team of Washington Post reporters covering James Meredith’s admission to the University of Mississippi after the campus and surrounding city had erupted into violent protests.

She left it up to the photographer she was traveling with to deal with the men since he knew how to negotiate the South, explaining that black reporters often had to come up with a ruse, disguising themselves as ministers, carrying Bibles, and hiding cameras and typewriters for fear of being attacked while working.

For 19 years she also served as a columnist in the Metro section of the newspaper, for which she said she was criticized for moralizing too much. “I guess that was a little bit of that preacher’s daughter in me,” she said.

In a Q & A session that followed, she was asked her advice for someone considering a journalism career

“It’s going to take courage,” she said. “Be yourself in calling forth your best self, knowing that you have all this potential, and use it in a way that does the most good.”